Together, we aren’t rare! Let’s talk about Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

CLICK HERE for the complete article in Ability Magazine

Twenty-five million people in the US are affected by rare diseases – many of them are genetic and life-limiting. One of these conditions is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), an unknown and neglected disorder of the connective tissue that can lead to severe disability. Over the last years, popular figures like Jameela Jamil and Mandy Harvey publicly spoke about their lives with EDS, which helped raise awareness. ABILITY Magazine recently interviewed Jameela, who shared her journey as an actress having several chronic illnesses. However, most people with EDS don’t stand in the spotlight, and their experiences might differ vastly. These people need to be heard as well, and this article is dedicated to all of them.

The yellow walls of my living room are spinning around me. I can’t feel my face or my tongue and collapse. It’s a sunny day – the last golden hour rays of light fall through my ceiling-high windows. “I think I have a stroke,” I say with unclear speech. My partner is overwhelmed; tries to catch me as my legs give out and I lie on my couch. I try to get back up, but I can’t feel my feet. “What is happening to me?” I whisper, with my tongue not working, sounding like I am drunk.

I was 24 years old in August 2010 when my life changed from one moment to another. A harmful medical treatment I received a day earlier started a myriad of symptoms and a four-year odyssey, which would cause me to leave my hometown Germany to find medical help in the US, began. Looking back at this time feels unreal and like it’s been a lifetime ago. And in a way, it is.

Today, I am sitting in my living room in San Francisco, working as a journalist after giving up my career as a research associate when I got sick. My writing focuses on telling the stories of people with chronic illnesses and disabilities through a ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ lens.

The last 11 years have been a journey like no other. I went from being a healthy and athletic 24-year-old who just moved into her first own apartment and started her career in a research lab in Germany to a disabled journalist with more than a page full of diagnoses, with the underlying cause being a rare disorder called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of rare, inheritable connective tissue disorders that affect the whole body. The most prominent sign is joint hypermobility and skin involvement. However, really any organ or system can be involved. As of now, we know of 14 different EDS types that vary in prevalence. The most common type is the hypermobile EDS (hEDS). All types but hEDS can be diagnosed via clinical examination and genetic testing. So far, there is no known genetic mutation for hEDS.

I was born with EDS, but growing up, I didn’t notice too many issues. I had small things, like frequent severe nose bleeds, causing me to end up in the ER; I was able to pop my hip in and out of its socket – this is called a dislocation – and I was constantly in pain, which doctors dismissed as growing pains. Additionally, my digestion was constantly off, which, again, was dismissed either as stress or as psychosomatic. I remember sleeping a lot as a child, often up to 12 hours, especially after I had participated in sports, and I didn’t know life without widespread pain that randomly jumped from one joint to another. Back then, nobody saw a connection between all my childhood issues, and they didn’t bother me too much. So I ignored them – until I couldn’t ignore them anymore in 2010 when my symptoms became so severe that I thought I might die.

But finding out what caused all my sudden issues wasn’t simple. It cost me four years of my life, which were solely focused on finding answers, and additionally a fortune of money for treatments, traveling to experts, and in the end, even flying across an ocean to seek help. Most healthy people disregard my experience as an exception, as something that couldn’t happen to them or any of their loved ones. But let me tell you something: My story isn’t unique. It’s the reality for most people living with a rare and unknown condition. And this article spotlights some of their voices.

Misdiagnosis

“If only someone had told Carol about EDS. It would have saved both mother and daughter much suffering, loneliness, and judgment” – John

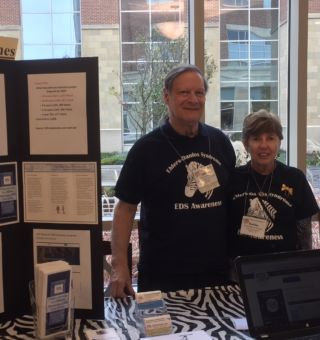

John is a man of his word. Everyone in the EDS community knows and values him and his work with his organization EDS Awareness. When he sends me e-mails, they all start with “Karina…” and often sound like a command. He gets straight to the point and doesn’t waste words on unimportant details. At the same time, John is one of the kindest and most honest people you can find. “I try to remember the phrase ‘We have one mouth and two ears so we can listen twice as much as we speak.’ I try to listen and understand but avoid judging,” John says. And John has been through a lot. He was 63 years old when his wife Carol died. Carol has been sick for more than 30 years, and she was never correctly diagnosed.

John met his wife while in college. They were married for 41 years. “You would think after all of that time, you would know everything there was to know about a person,” John says. Carol was a loving wife who wouldn’t complain about her symptoms that started shortly after they got married in 1967. She experienced issues with her joints, her intestines, her jaw and many other body parts, which resulted in constant pain. When her pain levels became worse in the 80s, John and Carol went to see many doctors, but none understood what was going on. “The doctors did not have a clue what she had,” John remembers. “Carol would describe affected parts of her body as shifted, twisted, crooked, and her favorite word discombobulated, meaning everything was zigzag and out-of-whack.”

Not being taken seriously, Carol felt discouraged and stopped telling doctors about her pain. All tests came back ‘normal,’ and there was no treatment or even a reason for her pain. “They just told her she was overly sensitive, exaggerating, or ‘it’s all in your head,’” John says.

Eventually, Carol was diagnosed with clinical depression, and her doctor checked her into a mental hospital. “During that time, they forced her to take over 13 pills,” John explains, “and one pill caused breast cancer.” After many rounds of chemo, she lost the battle and passed away in 2008 without ever being diagnosed with EDS.

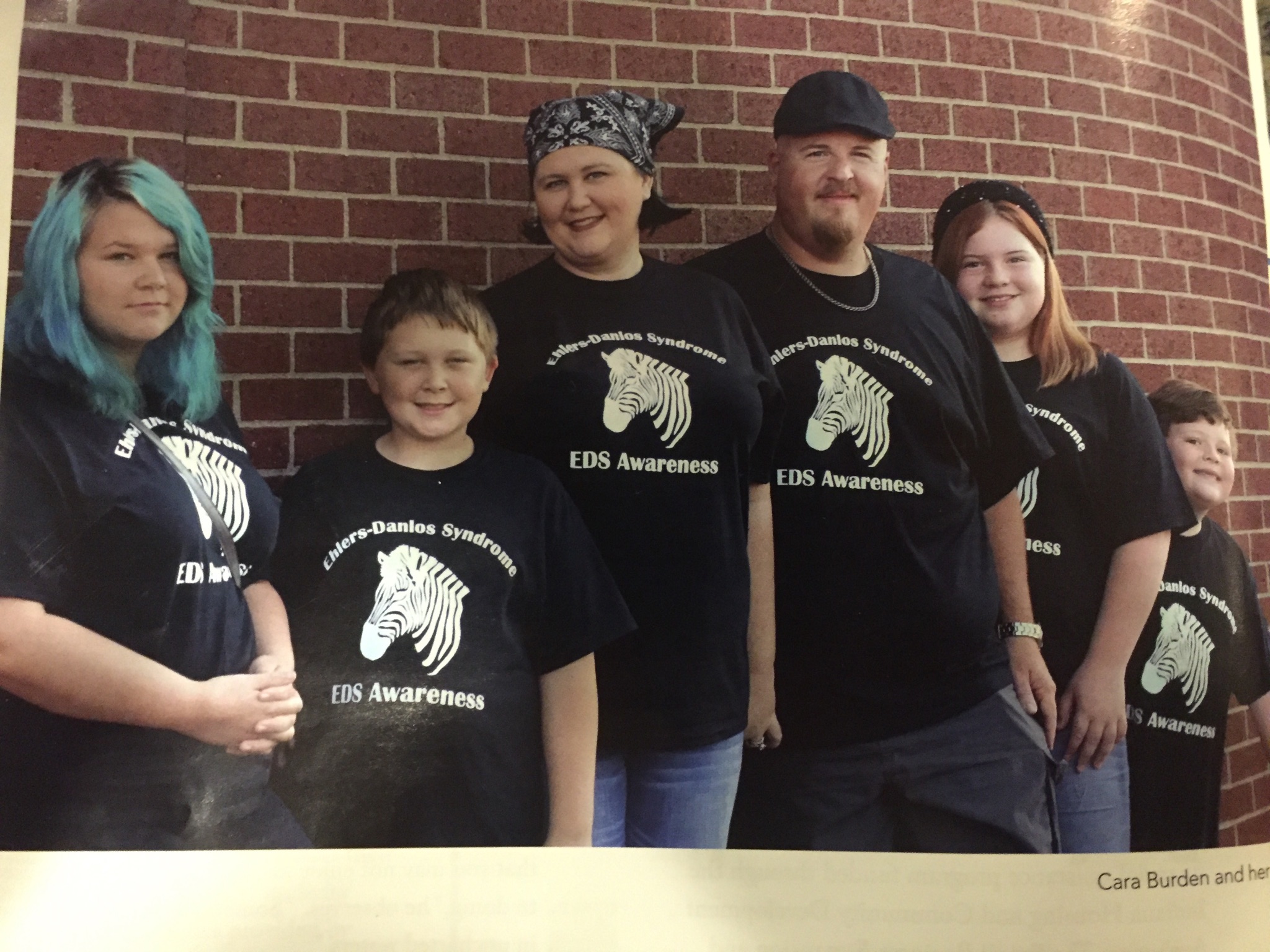

The same year, John’s younger daughter Deanna was found to have symptoms related to EDS. “After much research, Deanna discovered that she and her mother had many similar symptoms associated with what was called hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndromes,” John says. However, Deanna’s primary care physician dismissed her and said she looked fine and EDS was too rare. Father and daughter didn’t give up, and finally, Deanna was diagnosed with EDS the same year her mother died. The diagnosis explained both, her and her mom’s life-long struggles.

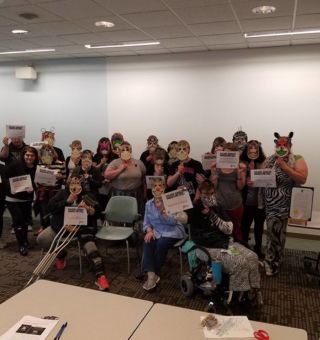

Today, John is 75 years old and runs his non-profit organization while caring for his severely ill daughter Deanna at the same time. “She lives an incredibly quiet existence: no talking, TV, computer, phone, music; no friends or even visitors, no trips; stares at the wall all day long. Left the house four times last year for doctor appointments,” John explains. John and Deanna started EDS Awareness together in 2011. “We decided a program to help my daughter with her EDS would be a good idea and keep me busy in retirement,” John says. And since chronically ill people often struggle financially, all of his organization’s programs are free.

This is John’s way of making other people’s lives better so that nobody has to suffer as much pain as his family. “If only someone had told Carol about EDS. It would have saved both mother and daughter much suffering, loneliness, and judgment. I do not have room here for all the details about how undiagnosed EDS harmed my wife and daughter’s lives. Just believe me when I say emphatically that if they had known about EDS, their lives would have been dramatically different!”

When I ask John what advice he would give to other people who care for a loved one with EDS, he says, “First, thank you for being an advocate for your loved one. You are embarking on a very challenging journey. Your loved one desperately needs your help. Listen to them and be there to help. Initially, you will discover that healthcare professionals, friends and relatives will not understand EDS. It is your job to educate them and protect your loved one from the world of misunderstanding, misdiagnosis and judgment.”

Like most people with EDS, I have received my fair share of wrong diagnoses as well. I spent the months between August 2010 and May 2014 mainly in doctors’ offices and hospitals. I can pride myself on the fact that I have visited every specialty in Germany. I visited experts for the rarest of rare conditions, and many experts thought they had the answer, but none actually did. Soon after all tests came back negative, they dismissed my symptoms as being ‘all in my head,’ which I later learned is a shared experience for all people that don’t quite fit the description of the well-known conditions doctors get taught in medical school.

“If you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras” is a phrase physicians learn during their training. This means that they should expect common diseases, not the rare ones, which prolongs the suffering for communities like mine. Fifty-six percent of all people with EDS receive a misdiagnosis – often a psychological one. And in all cases, getting a wrong diagnosis causes consequences, and like in John’s case, the most severe consequence: losing a loved one. The average time to actually getting diagnosed with EDS is 14 years. For many, it takes much longer than that; some never receive a diagnosis in their lifetime.

It only took me four years to get my EDS diagnosis. However, those were filled with self-doubts, anxiety, loss, and complete emotional exhaustion. At some point, if doctor after doctor tells you you are physically fine; if your family and friends start to belittle your symptoms and offer you advice, such as, ‘You just need to get out more and ignore your problems,’ you start believing them. Maybe you are just imagining your symptoms?

If I hadn’t followed my gut feeling, I wouldn’t know that I have EDS up until this day. I continued my search for answers, tried every possible treatment, from physical therapy to a healer. Nothing worked. My condition even progressed. What has started as a complex set of neurological issues with numbness and weakness of my arms and legs moved towards most of my joints in my body becoming unstable; I developed allergy-like symptoms to food and environmental factors; my blood pressure and heart rate started to fluctuate and made me faint; I had chronic pain in most of my joints; and my body was held together by braces and orthosis.

When no doctor in Germany would even take my case anymore, I decided to leave my home country behind and looked for help in the US. In the end, it was a mere coincidence that I ended up at a surgeon’s office who was a specialist for my medical condition. Four years after the onset of my acute symptoms and thousands of dollars later, I was finally diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

Many people underestimate the severity of misdiagnoses. It’s not an isolated problem affecting ‘only’ the millions of people living with rare diseases. It can happen to anyone. Research suspects that more than 10 percent of all diagnoses given to patients are wrong, and the incorrectly diagnosed conditions are often not even the rare and complicated ones but diseases like lung embolism, reactions to medication, different types of cancer or strokes. In the US alone, this affects 12 million people each year. However, those mistakes are often not even documented anywhere. So the actual number might be much higher. 200,000 Americans die from diagnostic errors every year. Misdiagnoses are the global epidemic that is not talked about even though they can have severe consequences. Over 30 percent of misdiagnosed patients either had life-threatening or deadly outcomes or permanent disability.

Receiving a correct diagnosis might be an important step for people living with rare conditions, but it certainly is only the beginning of the process. Syndromes like EDS are not well-known, and experts are sparse. EDS also leads to so-called comorbid conditions and complications, which are itself rare and largely neglected. Especially in the US, this complexity leads to large hurdles in terms of access to proper care.

CLICK HERE to complete reading the article in Ability Magazine