Meghan O’Rourke and The Invisible Kingdom

As part of our monthly Funny Bone Newsletter, journalist Karina Sturm had the pleasure of speaking with Megan O’Rourke, a fellow Zebra, but more importantly, journalist and author who recently published the bestselling book “The Invisible Kingdom,” highlighting the challenges of living with several chronic conditions, including Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Meghan O’Rourke is an award-winning writer, poet, and editor, and her work has been published in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and Slate, among others.

Karina Sturm:

Meghan, can you tell me a bit about your new book, The Invisible Kingdom, and how it relates to the EDS community?

Meghan O’Rourke:

The Invisible Kingdom tells my own story of getting sick “gradually and then suddenly,” to quote Ernest Hemingway, with mysterious symptoms that roamed my body, including things like joint pain, dizziness, fatigue, brain fog, pain, and a racing heart. I began visiting doctors searching for answers in my early 20s, but it took more than a decade before any one of them even believed I was sick. In the end, I was diagnosed with an autoimmune disease, untreated Lyme disease, POTS, and, eventually—after more than 20 years of active seeking answers!—hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. It took a long time to understand what was happening to me. Doctors told me my labs looked fine. But my life was slowly dissolving into near-constant pain and suffering that I had no name for. The book aims to capture that lived experience and also to offer a framework for why, in our hyper-diagnostic age, it is so had to get a diagnosis of things like EDS.

Karina:

Actually, this Hemingway quote was what immediately pulled me into your book. Is Hemingway an author who influenced your writing? I always liked his “factuality” and his very “straight-to-the-point”-way to express himself.

Meghan:

Earlier in my writing life, his clarity and ability to evoke a scene very deftly and concisely really did influence me. I love the music of his sentences. But I think of Susan Sontag, author of the great Illness as Metaphor, as in many ways the presiding influence of this book.

(Image by David Surowiecki)

Karina:

Your experience of seeking answers for decades is sadly normal for people with EDS. Can you tell me a bit more about your own journey to finally getting diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and all the comorbid conditions?

Meghan:

The experience was lonely, frustrating, maddening—even traumatic, a word I don’t use lightly.

I endured two kinds of suffering: The physical challenges of living with my illness, and the terror and mental pain of enduring the utter invisibility of my disease to others, which itself nearly killed me.

I was willing to endure a lot, but I wanted the dignity of my experience to be recognized. The fact that my suffering was dismissed robbed my illness of any meaning. I couldn’t adjust to my new limitation on my own terms because I was caught up trying to get others to believe me. And of course the ignorance and dismissal I encountered from medical providers made me despair that I would ever get help or answers, given that no one seemed willing to acknowledge that anything I was describing was biologically real and not triggered by, say, anxiety.

Karina:

I can relate a lot to the word “trauma.” The constant gaslighting and being doubted by medical professionals and the people around me caused me PTSD, which still, years after getting diagnosed, affects me every time I see a new doctor. So, now, The Invisible Kingdom isn’t your first book that deals with chronic illness, is it? Can you tell me how and why you incorporate your experience with EDS/chronic illness/disability in your books?

Meghan:

Yes, I wrote about my illness experience in my book of poems and lyric essays, Sun In Days. I write about illness in that book part to understand it for myself, to take some time to reflect on an experience that had been really puzzling, and try to find language for it. One of the challenges of being sick, for me, was figuring out how to use words to communicate it: “Fatigue” and “pain” and “brain fog”—other people’s minds slide off these words, unless they have experienced what we have. But I wrote The Invisible Kingdom explicitly to try to galvanize a broader conversation about the ways we stigmatize invisible illnesses, to make them more visible and unignorable, and to, I hope, bring some comfort and validation to others who have their own versions of this lived experience. I want the book to be both a call to arms and a source of comfort and recognition.

Karina:

Yeah, becoming “visible” is something I have been working on for a while now too. That’s the reason why I made We Are Visible, my film about people living with hEDS. However, I am always wondering if I actually reach a “mainstream” audience with my advocacy. You seem to have achieved exactly this. Can you share some of your wisdom on how you reached a healthy, non-disabled audience and made them feel more comfortable around the conversation on illness and disability?

Meghan:

Great question. In addition to being a memoirist and poet, I’ve written journalism for twenty years and had a weekly column for a long time at Slate, so my professional career had trained me to translate ideas and experiences to a broader audience, using storytelling and (I hope) good writing to bring the reader through a story they may not know they want to read. During my work on this book, I spent a lot of time thinking about how to pull caretakers and family members and colleagues and medical professionals along. One answer was to couch it as a kind of mystery and to work hard on building some sense of suspense and investment. Another was to show that this is not my problem or your problem, right? It is not “sick people’s” problem. Illness is the mortal condition and it is an ethical act to bear witness to one another’s suffering. I tried to make clear that the silent epidemic of chronic illness is a societal issue we should all be invested in.

(Image by Meghan O’Rourke)

Karina:

That’s a very good approach! I hope your work reaches a much broader audience because this certainly benefits us all! Personally, writing is much more than a job for me. It’s a way for me to cope with my conditions. I read that it is the same for you. Can you tell me how you got into writing and how writing helps you to cope with chronic illness?

Meghan:

I began writing when my mother gave me a journal when I was five years old and pretty much always knew I wanted to be a writer. I find that writing things down helps me figure out how I think and feel and to make space for the untidiness—the mess, the ups and downs, the private reckonings—of living with EDS and other conditions. I also used a journal to keep track of my symptoms and what alleviated or worsened them–on a practical level this was really crucial for me.

Karina:

I started writing journals in 4th grade but actually was discouraged from becoming a writer by a teacher, but picked it up again when I became ill and then officially switched to journalism after having to give up my career in research. I think for me, it was a coping mechanism first and a career after. However, when I have a really bad flare-up and feel too sick to write, I get super frustrated and sad. How do you deal with days where you don’t feel well enough to write? Is there a trick you use to still be able to put some words on paper?

Meghan:

I try to be patient. Life as a chronically ill patient means that we can’t always live the life of hyperproductivity we see advertised around us, right? And that life is probably based on some pathologies anyway. But when I was at my sickest and really couldn’t write for months on end, I had to find a way to hold on to my identity as a maker and artist—for my own sanity. So I told myself that my “writing” job was to write one to three sentences a day. The results tended to be aphoristic and compressed.

Karina:

You should publish whatever came out of those one to three sentences a day! This would show very well how life as a chronically ill person sometimes interferes with really everything. What’s one thing you have learned about yourself and about the chronic illness community while writing this book?

Meghan:

We are so much stronger than we, or anyone else, knows!

Karina:

Yes, we definitely are! And you are proving this with your book. It’s so crucial for the community to have so many advocates that use their passion and talents to represent us publicly.

What’s the message you hope people with but also people without the chronic illness/disability experience will take away from your book?

Meghan O’Rourke was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

(Image by David Surowiecki)

Meghan:

I hope it will help them realize that there are millions of us who need to be seen and heard. I hope that this book might help readers better understand what their spouse or friend or colleague is going through; I want them to know that it is real, and it is debilitating, and that we shouldn’t dismiss a loved one’s pain or symptoms because they do not yet have a name, or a diagnosis. We shouldn’t look away because it is uncomfortable to contemplate chronic illness. Not every illness has a cure; not every illness can be overcome. Some we need to live with, and those who live with them need our support and understanding.

I hope, too, that the book might move physicians and scientists to consider the idea that patients often have crucial wisdom to offer, and often respect, revere, and depend on their doctor’s validation, even when answers are in short supply. Finally: More funding and research, please!

Karina:

That’s a very good takeaway message. Many of us in the EDS community don’t have a great support system, mainly because EDS is so misunderstood by not only medical professionals but also the people around us. I was lucky. I did lose a lot of friends, but the main core and also my family never stopped supporting me. But that’s a privilege not everyone has, and I hope that your work contributes to a better understanding! Do you plan to use your platform more to raise awareness for people with EDS in the future? If so, tell us a secret of what you plan?

Meghan:

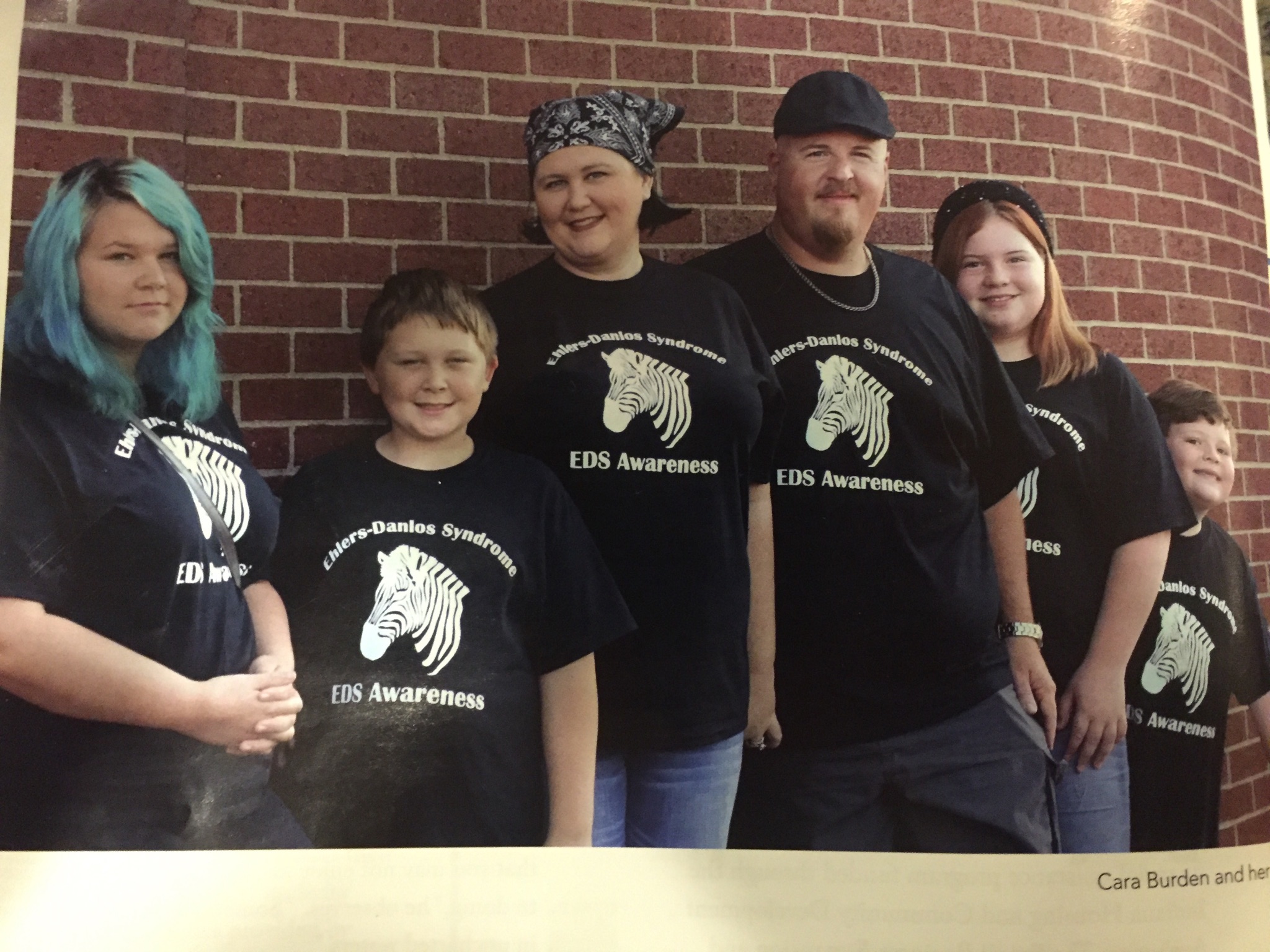

Yes. I only learned I had EDS near the end of writing my book. I’m hoping that one of my next big essays is about EDS. My son has EDS too and I am more of a passionate advocate than ever watching his struggles and successes. So I hope to write a long essay about EDS for a national magazine soon…

Karina:

That sounds exciting! Please share whatever work you produce next with us. We’d love to support your future way! Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me today and supporting the Chronic Pain Partners (EDS Awareness) advocacy work! We appreciate you and your book a lot! And before we end, please tell us how the community can support you?

Meghan:

I’d love it if you considered purchasing The Invisible Kingdom or taking it out of your local library and leaving a review on Goodreads or Amazon. I’m just starting to speak to medical organizations and patient groups and always eager to learn of great opportunities to spread the word so we can change the visibility of EDS and create the knowledge base and community we all need so urgently. I’m really happy to support the work that is already out there, too.

You can buy The Invisible Kingdom in book stores or on Amazon.

Find out more about Meghan and all her books via her website: https://meghanorourke.com

Or check out Meghan’s Social Media:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/meghanorourkewriter/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/meghanor/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/meghan-o-rourke-266880b/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/meghanor

And sign up for the Funny Bone Newsletter to receive more original content like this interview!

I Thank You both for this eloquent discussion, and have put this book on my pertinent reads list since it appears Meagan has captured to paper a lot of what I have thought and would not or could not say… and probably a lot that I had thought and have forgotten or had stolen from me by age, brain fog, pain, (you folks know the drill!).

It saddens me to hear that Meghan’s son has acquired this also, I am glad that now she has been diagnosed she may be able to help him through the journey. But would just like to caution her that since it is even more rare in males that his journey will tend to be very different and will present unique challenges.

Not worse, because it is troublesome for all of us, and yes worse for some more than others, but the medical community when presented with a male specimen tend to like to add to the disbelief with statements like “EDS is a woman’s disease , you can’t have that!” or when plagued with pain and needing to lick your wounds to try to regroup being told “Man -up!- Don’t be such a Sissy!” and things of that sort.

When I used to be more active in the EDS community I always tried to give everyone all the credit they deserve for having to live with the things we do … But I always gave our female counterparts the extra credit they deserve for the having to put up with the extra burdens we men did not have to face such as childbirth, periods, as well as the other societal issues that are faced, but there is an added layer of loneliness and isolation because although our disease is rare… the number of males to discuss this with is akin to trying to round up Bigfoot to have a conversation with and to compare notes.

And yet when presented with a young male with questions for me I do not know what to tell them as far as what to do or not, I can tell them how I arrived at this point, but I am remiss to recommend some of the things I did to manage as well as I did because the process by and large pushed me to the edges of Suicide , Depression, and complete mental breakdown… And frankly, having lived does not feel like a victory, and makes me wonder if possibly not being as strong may have been the better option.

And with that said, I hope your month goes well, Thanks again and I look forward to what things you have to say in the future!