What Two New Studies Say About the Head, Neck, and hEDS

People with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome have heard for years that their symptoms are “in their head.” In one sense, that may be true—but not in the way we all hate to hear. When it comes to symptoms like headaches, nausea, dizziness, brain fog, visual disturbances, neck pain, fatigue, and more, the problem IS in our heads—and upper spine. For some, these symptoms are so severe, they confine people to bed. Yet when imaging is ordered, patients are often told nothing is “bad enough.”

Part of the problem is that there hasn’t been a shared definition of what “normal” even looks like in the head and upper spine. Some experienced doctors based their idea of “normal” on years of observation, and those measurements circulated like a secret code. Doctors often dismissed patients who suspected they had craniocervical instability, cervical spine instability, atlanto-axial instability, or another problem in the same area because their measurements weren’t abnormal. Other doctors often disagreed with this assessment, leaving patients stuck in the middle without a diagnosis and feeling a strong urge to pull their heads off and drop-kick them into the nearest trash can.

Until recently. In 2025, two new papers began to answer two critical questions:

- What are normal measurements for the head and upper spine?

- Are the heads and upper spines of people with hypermobile EDS (hEDS) measurably different?

Let’s look at what they found. Both results could be helpful in identifying problems in the head and upper spine sooner and could add to the signs of hEDS, helping with diagnosis while the genetic cause is still a mystery.

Finding Normal to Define Abnormal

The first paper, Radiographic Indicators of Craniocervical Instability: Analyzing Variance of Normative Supine and Upright Imaging in a Healthy Population, aimed to do something that seems simple: measure seven important angles and distances in the neck of people who have no known issues with their cervical spine If we can figure out what normal looks like, then measurements outside those ranges would be abnormal, and a consistent evaluation could be done between doctors and medical centers. The seven angles they measured in 72 people are listed below.

| Full Name | Abbr. | What It Measures |

| Clivo-axial angle | CXA | How the base of the skull meets the top of the spine; skull-spine alignment |

| Basion-dens interval | BDI | Distance between the base of the skull and the top of the second cervical vertebra (C2/axis) |

| Basion-axis interval | BAI | How far forward or backward the base of the skull sits relative to the cervical spine; front-to-back alignment |

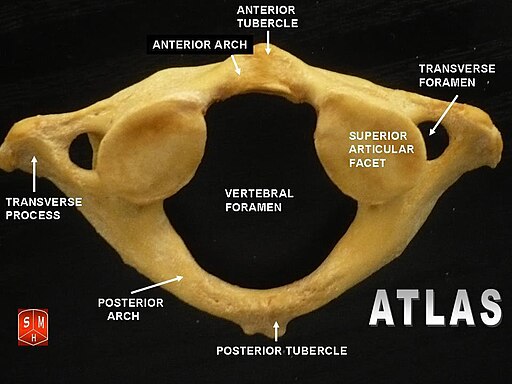

| Atlanto-dental interval | ADI | The space between the first C1/atlas and C2/axis |

| Perpendicular basion to the inferior aspect of C2 | pbC2 | How far the base of the skull projects toward the spinal canal, using a reference line along the second cervical vertebra; how much the skull base is moved toward the spine Also known as the Grabb-Oak measurement or Grabb’s line, this is measuring the distance from a fixed object to a line drawn between two other objects. |

| Hard palate to C1 | HPC1 | The relationship of the nasal cavity to the upper cervical spine, specifically C1/atlas |

| Hard palate to C2 | HPC2 | The relationship of the nasal cavity to the upper cervical spine, specifically C2/axis |

This study used the existing images of 72 people without cervical spine injuries, issues, or abnormalities. The researchers used four different positions and two different imaging techniques for the measurements: extension x-ray, flexion x-ray, and neutral x-ray, and a supine computed tomography scan (CT scan).

Several measurements changed significantly depending on how the image was taken. In other words, a value that looks “normal” on a CT scan may not fall in the same range on an extension x-ray. It means measurements must be interpreted in context, not in isolation. For example, if a doctor is measuring someone’s HPC2, they should know that the difference between the supine CT scan and the neutral x-ray is significant—so if one falls into the “normal” range, it might be worth looking at the other. These differences have been added to the chart from above.

| Full Name | Abbr. | What It Measures | Significant differences in…* |

| Clivo-axial angle | CXA | How the base of the skull meets the top of the spine; skull-spine alignment | EXR & SCT EXR & NXR EXR & FXR |

| Basion-dens interval | BDI | Distance between the base of the skull and the top of the second cervical vertebra (C2/axis) | EXR & SCT EXR & FXR |

| Basion-axis interval | BAI | How far forward or backward the base of the skull sits relative to the cervical spine; front-to-back alignment | FXR & SCT |

| Atlanto-dental interval | ADI | The space between the first C1/atlas and C2/axis | None |

| Perpendicular basion to the inferior aspect of C2 | pbC2 | How far the base of the skull projects toward the spinal canal, using a reference line along the second cervical vertebra; how much the skull base is moved toward the spine Also known as the Grabb-Oak measurement or Grabb’s line, this is measuring the distance from a fixed object to a line drawn between two other objects. | NXR & FXR FXR & SCT EXR & FXR |

| Hard palate to C1 | HPC1 | The relationship of the nasal cavity to the upper cervical spine, specifically C1/atlas | FXR & SCT EXR & SCT EXR & NXR EXR & FXR |

| Hard palate to C2 | HPC2 | The relationship of the nasal cavity to the upper cervical spine, specifically C2/axis | NXR & SCT NXR & FXR EXR & SCT EXR & NXR EXR & FXR |

Of the seven measurements studied, CXA emerged as the most reliable across all four imaging types. HPC1 and HPC2 also performed reasonably well. Other measurements varied more depending on position.

The normal ranges for CXA are:

- Extension x-ray: 151.02º to 187.58º

- Flexion x-ray: 130.88º to 180.16º

- Neutral x-ray: 135.29º to 179.37º

- Supine CT: 134.39º to 181.95º

Previously, some experts cited 145°–160° as a “normal” CXA range. Now, we have published ranges across multiple imaging positions, even if they come from a small sample. It’s not the final word on head and upper neck measurements, but it’s the first step toward consistency.

For more information about cervical spine instability, Chronic Pain Partners’ CSI patient guide has great information to read and share with your doctor.

HEDS vs. Non-hEDS: Structure vs. Posture?

The second paper, Head Posture and Upper Spine Morphological Deviations in People With Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome, asked different questions: are people with hEDS structurally or posturally different? Do they have more deviations in their anatomy than those without hEDS? This study examined 27 people with hEDS and 39 without hEDS using lateral cephalograms and cone-based computed tomography (CBCT). It then compared the findings by gender, age groups, and people with hEDS and those without. They looked at craniofacial anatomical measurements, head and neck posture angles, and structural deviation of the upper cervical spine.

The Surprising Finding: No Differences

When researchers compared anatomical measurements and posture angles, they found no significant differences between hEDS and non-hEDS groups, men and women, and different age groups. (Unfortunately, like many medical studies, transgender and non-binary people were not included.)

Baseline anatomical structure and posture probably don’t account for the symptoms many people with hEDS experience.

Where the Differences Are: Deviations

The study found that more than half of the hEDS group (51.9%) had some kind of anatomical deviation in the upper cervical spine, while, in striking contrast, only about 15% of the non-hEDS group did. When researchers broke this down further, they found that certain deviations—particularly posterior arch deficiencies (PAD)—were more common in people with hEDS.

PAD includes partial cleft and developmental gaps in the posterior arch of C1 (the atlas). A partial cleft means the arch did not fully fuse during development. In many people, this causes no symptoms and may never be discovered. In medical language, this is often referred to as spina bifida occulta, “occulta” meaning hidden.

The study also identified C2/C3 fusions in some participants. However, those numbers were small enough that statistical analysis suggested the difference could be due to chance. Why does it matter? Not every visible difference is meaningful, but when a structural pattern appears consistently in one group more than another, it deserves attention.

A Foundation, Not a Finish Line

We now have published reference ranges for several craniocervical measurements, and we know that some measurements can vary significantly depending on the imaging modality. We also now know that people with hEDS are more likely to have certain upper cervical anatomical variations. All of this, taken in context with other symptoms and signs, could improve the care for people who may be struggling with head and upper spine pain. The increased presence of deviations could be another clue in the diagnostic journey for hEDS. While neither paper offers definitive answers, both push the field toward more consistent evaluation and away from subjective guesswork.

Kate Schultz

January 2026

What did you think of this content? Send us a rating or add a comment below—or do both!